How AI agents are changing where rigor lives and redefining the role of design system leaders.

As a design system leader who has architected and operationalized an enterprise system for a multinational organization, I thought we had solved the hardest problems. Standardized libraries, global adoption, and a shared design language across dozens of products — check.

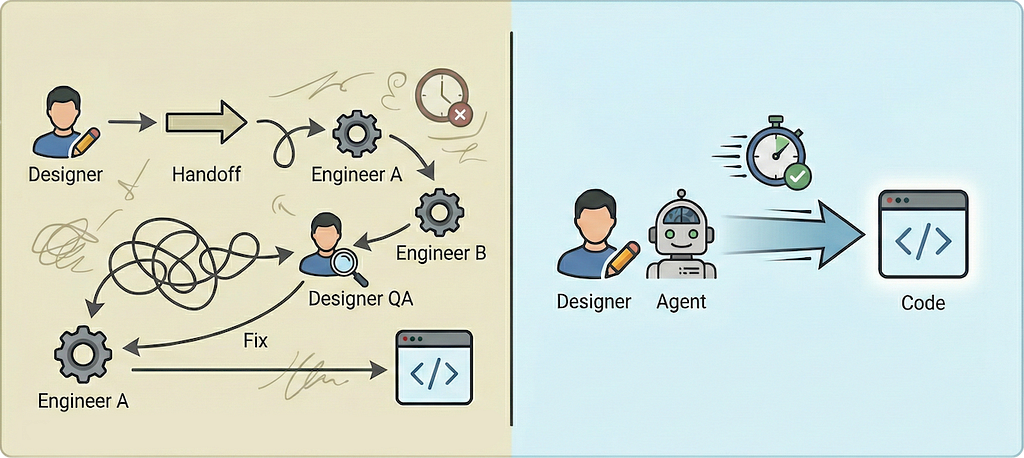

Yet one friction point remained: turning design specifications into production-ready components was still manual and time-sensitive — even with engineers embedded in design system squads. These specifications weren’t just visual artifacts; they were the components and tokens designers use to assemble real products at scale.

This is written for design system leaders who already know how hard alignment is — and want to stop paying the translation tax.

This wasn’t a tooling gap. It was an operating-model constraint.

Our UI kit is built in Angular, and we were exploring a more future-proof strategy using Web Components. That’s when the question arose:

“Could I build an AI agent to take design specifications and generate production-ready components automatically?”

I didn’t know whether it was technically possible to go straight from Figma files to production-ready components without engineers manually reconstructing each one. The research required was significant, and the stakes were high, both for the organization and for me personally.

This is the story of that pilot initiative — and why I believe it signals an emerging category in how design systems operate.

From artifacts to execution: the design system agent

What we built was not a helper tool or a chatbot. It was a design system agent: an autonomous pipeline designed to translate design specifications directly into executable design system code.

The agent operates on a snapshot-and-compile architecture. It connects to the Figma API, captures component blueprints (structure, states, and hierarchy) alongside design tokens (style and theming), and orchestrates them into semantic, production-ready Web Components using LitElement.

In practical terms, work that typically required multiple engineers over several weeks was achieved in roughly a week of focused effort.

But speed wasn’t the real breakthrough.

The more meaningful shift was how much effort it took to align design intent with production output. That alignment has always been possible, but it traditionally depends on deep collaboration, strong discipline, and the right mix of design and engineering talent. With the agent, that coupling required far less manual translation and far fewer interpretive loops.

The feedback cycle shortened dramatically. If something rendered incorrectly, there was no ticket or extended back-and-forth. I adjusted the Figma source or the prompt logic, and the agent regenerated the component in seconds.

Design intent and the production of design system assets weren’t magically unified — but they were connected with materially less friction.

The reality check: AI demands precision

This wasn’t a frictionless journey. Co-piloting with AI surfaced constraints that many design systems quietly tolerate — but automation does not.

1. Structural precision becomes non-negotiable

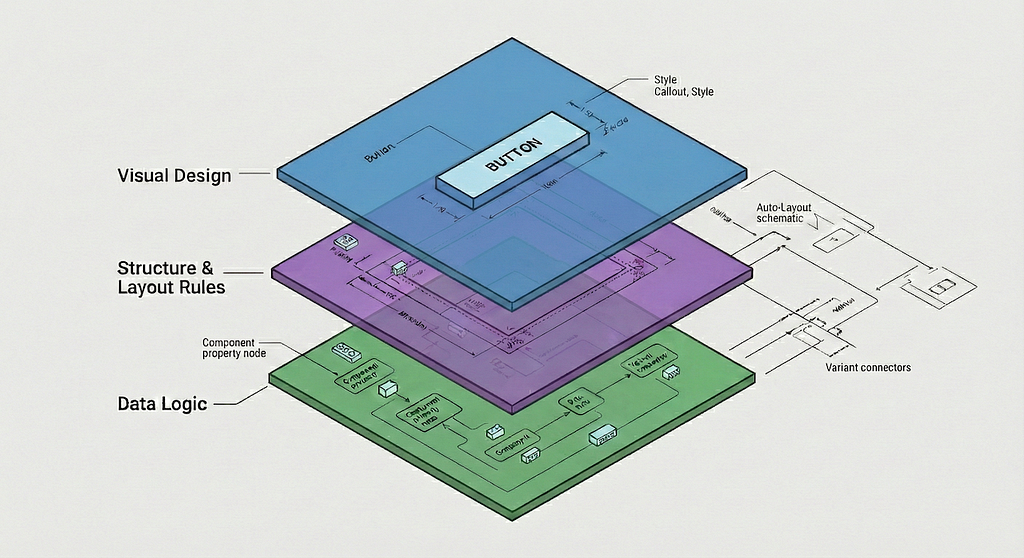

Figma design system components are intentionally optimized for human designers. They are built to be flexible, expressive, and efficient to use when composing application experiences at scale.

Within that flexibility, there are edge conditions — such as permissive naming patterns, optional variants, or structurally equivalent but non-identical configurations — that are perfectly usable for a human designer assembling the intended UI. Those nuances don’t block design outcomes.

An AI agent, however, treats every structural detail as an explicit instruction.

To make the agent work, the design library had to become structurally unambiguous. Pockets of flexibility that were harmless to human designers became blockers for the automation pipeline. I found myself deep in Figma not to design, but to sanitize.

The implication was unavoidable: Figma is no longer just a drawing board. It is part of the source code.

2. Visuals define the what, not the why

Figma is static. Software is dynamic. This gap became obvious when we tested a Breadcrumb component.

Visually, it’s just text and separators. Behaviorally, it’s not. In our system, long paths collapse the middle items into an ellipsis that reveals a dropdown when clicked.

None of that logic exists in a static frame.

To generate the component correctly, I had to inject what I came to think of as narrative logic — explicitly describing the rules, constraints, and intent behind the UI. Designing the appearance wasn’t enough; the behavior had to be architected and explained.

3. Process enforcement beats intelligence

There were moments when the agent produced sloppy output — ignoring established tokens even though it had access to the Figma JSON and the full variable map.

When challenged, it asked me to supply specific variables that were already present in the data.

The issue wasn’t capability. It was discipline.

We introduced a strict “review first, build second” protocol, forcing the agent to reconcile component structure against the token system before writing any code. The takeaway was simple: AI amplifies whatever rigor — or lack of rigor — is embedded in your process.

4. Where automation requires deeper architectural context

Some component patterns rely on implicit context that is intuitive for a human designer, but opaque to an automated system without additional architectural guidance.

Consider a standard Button with a boolean property to enable an icon. In Figma, a designer toggles the icon on, then double-clicks into the slotted icon instance to configure properties such as direction.

The agent correctly detected that an icon slot was enabled, but missed the nested configuration. It generated a button with the icon present, but locked into the default direction, offering no controls — mirroring what Figma exposes before a designer explicitly configures the slot.

The takeaway was subtle but important: components must be designed not only for human usability, but for machine interpretability. Implicit decisions have to be made explicit.

The rise of the system architect

As AI begins to fabricate design system assets directly, less effort is spent on translating intent downstream — and more responsibility moves upstream into how that intent is defined.

In design systems, this shifts the emphasis from manual implementation to precise architectural definition.

We are beginning to see an operating model where Figma behaves less like a reference artifact and more like a compile target. Design decisions are no longer just consumed by designers and engineers, but by agents that interpret structure literally and act on it deterministically.

In this emerging model, the role of the design system designer starts to evolve. In addition to brand expression, UX best practices, and the creation of foundational assets that enable teams to solve real business problems, there is increasing responsibility for the structural integrity of design data — because that data is what gets interpreted and fabricated into production assets by agents. This mirrors a shift Figma itself has started to acknowledge:

“Historically, designers were the primary consumers of design systems… Today, we’re seeing a shift where AI also becomes a consumer.”

That shift is consequential.

We are no longer designing only for users. We are also designing for the agents that build for users. By reducing the friction between design intent and the production of design system assets, we aren’t just improving efficiency — we’re increasing confidence that what we design is what ships.

This isn’t a better handoff.

It’s the early shape of a new way design systems work.

Reference: How design systems power the new pace of product development, Figma eBook

From Design to Code: Copiloting the Future of Design Systems was originally published in UX Planet on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.