It’s no secret that, when it comes to Choice Architecture, defaults can be a powerful tool. Many research studies have documented that users are more likely to accept an option if the choice is filled in for them. Like any other design tactic, however, its effectiveness varies depending on context and implementation.

Fortunately, there’s a growing body of academic research that illuminates exactly what makes defaults effective, including recent work by Eric Johnson, a Professor of Business and Decision Science at Columbia University. It turns out that there are three factors that drive the effectiveness of defaults. Understanding these factors is essential to determining if defaulting is the right approach for a particular touchpoint and, if it is, how a default can be amplified to change behavior or simplify a decision. Let’s explore the three factors in making a default effective:

Defaults help people avoid thinking about difficult things

The first reason defaults are effective is pretty clear: they reduce the interaction cost of making a selection. Defaulting saves the effort of reading, typing, or navigating to another option. As UX designers, we know people are always looking to save time and effort.

Beyond saving time and effort, it turns out defaults have extra power when we ask users to make a selection about something that is difficult to think about. Just like people tend to avoid doing things that are difficult, they also avoid thinking about difficult things. Here, too, there’s more nuance. What counts as difficult can come in a couple of forms:

- A topic that is uncertain (i.e.: a calculation or an abstract topic)

- A topic that is emotionally unpleasant (i.e.: a negative event)

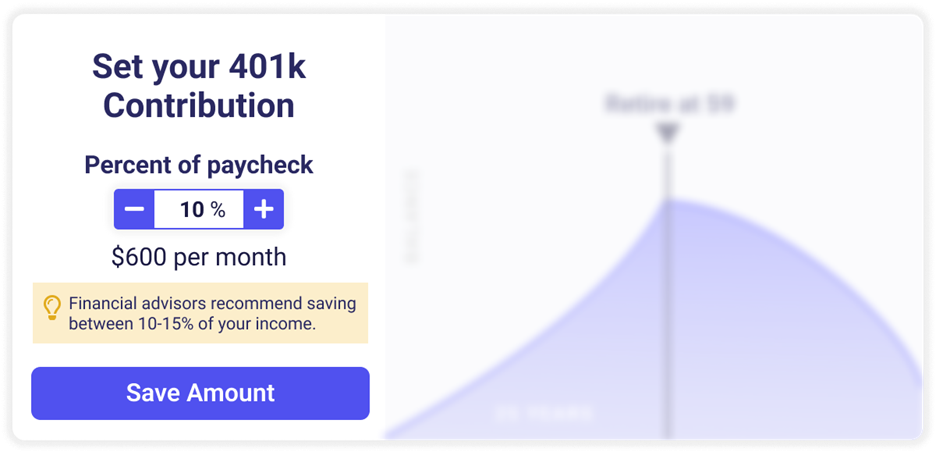

An example of the first type of difficulty is when someone is being asked to decide what percentage of their paycheck, they want to set aside for their 401k or retirement account. It’s hard to know what the correct contribution level is since people don’t necessarily know how much saving each month will support them in the future. Accepting a default offers a way to avoid making those calculations.

Difficulty can also take the form of something that is simply unpleasant to think about. This is the reason defaults have been documented to be so effective in opting people into organ donations.

It’s not that deciding to be an organ donor requires complex calculations. Rather, it requires us to think about some unpleasant things. Namely, dying and what happens to your body after that. Applying defaults in settings like this enables people to forgo those thoughts and get the decision over with.

Tips for Designers:

- Audit your experience for decisions, selections, or steps that are complex. Invest in finding a reasonable default for these steps and apply them.

- Evaluate whether there are any decisions in your experience that require users to think about something that might be unpleasant. Find defaults that may work to help users avoid thinking about these things.

- If you have a high degree of confidence that a certain option is best for users, increase the physical interaction cost of opting out of the default. This will increase the percentage of users that accept the default.

Defaults change the way users see their other options

Defaulting doesn’t just help people avoid thinking about hard things, it actually changes their preferences about the options available to them. For example, it’s easy to assume that most people come to every decision with a strong opinion about what’s best. The reality is that for most things, we make up our mind at the point when we are asked to decide. This is what psychologists call an “assembled preference”. What this means is that the value we attach to an option can change depending on how it’s presented.

Once someone sees an option defaulted, they actually establish a preference for that default. As unbelievable as it sounds, simply selecting an option increases its value in people’s minds. There are three well-researched cognitive biases behind this:

- The Endowment Effect: the tendency to place a higher value on something if we have it in our possession than if we don’t.

- Framing: the tendency to value the same options differently depending on which parts are highlighted in their description.

- Anchoring: the tendency for a person’s estimate or valuation to gravitate towards the quantity they saw first.

When we default an option, people begin to think about the positive attributes of that first option. When they think about moving away from the default to another option, they’re primed to think about what they’ll lose by selecting something else.

Let’s return to our Retirement Savings Calculator example. There are pros and cons to contributing more or less aggressively to your 401k. If a person puts aside more of their paycheck each month, they’ll be able to retire earlier. If they save less, they’ll have more money to spend on stuff they want right now. Presenting a default choice influences the salience, or prominence of these benefits in a person’s mind, and impacts how aggressively they save for the future.

If the savings rate defaults to a level that allows users to retire at 59, it will call to mind the fun things they’ll be able to do while they’re relatively young. If they decrease their contribution, they’ll be more aware of the additional years they’ll have to work to retire. On the flipside, defaulting to a lower savings rate leaves more money in a user’s pocket each month. In this case, people will be more likely to feel the pinch of their paycheck shrinking each month as they increase their savings rate to retire earlier.

Tips for Designers

- Consider pairing a default with messaging that emphasizes its benefits.

- Increase the visual prominence of a default to ensure people see it selected first, and therefore, become anchored to it.

- Consider offering a decoy option (one that is clearly inferior) in order to amplify the value of a default choice.

Defaults imply a recommendation

The third thing that makes defaults effective is that they can be perceived as an endorsement or recommendation of a particular choice. For example, if we default to a five percent contribution level in a retirement fund, users may assume this is an acceptable level. This Endorsement Effect is especially powerful if a person trusts the brand they are interacting with, and if they perceive the brand as knowing their needs and having their best interests in mind.

Tips for Designers

- If there is strong reason to believe a user will be satisfied with a default, you can amplify the Endorsement Effect by making it clear the default is a recommendation.

- Provide brief messaging around why a default has been selected and why a customer may want to stick with it. For example, let users know that a defaulted savings rate is agreed on as a good minimum by most financial advisors.

- Look for opportunities to build credibility in your brand at the point your customer is being asked to make a decision. People are more likely to accept a default recommendation if they trust your brand.

Other factors that can influence the impact of defaults

Does each of these three effects ensure that defaults will always be effective? No. Actually, there’s one important factor that determines how likely a user is to accept a default: how experienced they are in making a decision or how strong their preferences are. If your users know what they need (and are invested in the decision) they’ll override the default. In these settings, imposing unnecessary defaults or making them too hard to adjust will create a frustrating experience. Unfortunately, that frustration will likely grow the more they use your product.

Defaults that are overly generic can also backfire. As we’ve discussed, defaults have a powerful influence on users’ selections. If a default succeeds in helping people move through a decision quickly, but doesn’t help them select something that is right for them, their long-term satisfaction with your product will suffer.

An approach that can help with this is to personalize defaults. Rather than applying one default across all customers, leverage what you know about your users to default to an option that is right for their particular needs. This could simply mean remembering what a user has selected the last time they interacted with your product. For products that aren’t used frequently, you can try to leverage data from a user’s profile or data that they’ve provided in other parts of your experience. For example, if you’re designing a benefits enrollment tool, you may want to default customers with young children into plans with more robust coverage since small children tend to need more medical care.

Summary

Understanding the psychology of how and why defaults are effective is critical to getting the most out of them. Research shows that defaults function in three ways: they eliminate the friction of having to think about difficult things, they anchor people to a certain value or option, and they can be perceived as a recommendation. However, defaults are most influential when they are personalized and when they are provided for people with less experience making a decision.