In this article, I want to share tips on creating the first version of a career progression framework that fits your team and company, and how to get the most out of it. This advice is especially useful for new design managers.

Starting as a design manager can be exciting and a bit tough, especially for beginners. Beyond project leadership, you must champion the design’s significance, shape a clear vision aligned with business goals, and uplift the team morale.

A well-crafted career progression framework can become an essential tool to overcome a significant number of challenges of design leadership.

What is CPF and why do all design teams need it?

As Design Managers, we play a crucial role in maintaining a motivated team and fostering professional growth. Alongside factors like design influence, fair compensation, and quality work opportunities, designers’ motivation is high when the company helps them with skill development and provides career growth.

Common mistakes, such as a lack of training or generic training not tailored to personal growth, arbitrary promotions, or neglecting promotions altogether, can significantly reduce the designer’s motivation. It’s not unusual to see two designers with similar roles and skills end up at different career levels and salaries at the same company due to differences in self-promotion during hiring.

A well-constructed Career Progression Framework (CPF) comes in handy for managers. It allows for objective assessments of designers’ levels and skills, facilitating the creation of personalized development plans and establishing crucial team guidelines. You can use these guidelines to foster a culture of creativity and support, providing a clear path for individual growth within a united and motivated team.

In simpler terms, a Career Progression Framework allows you to transparently communicate to your team how they can achieve success in the company. The “rules” for success are clear and apply equally to everyone.

Crafting the framework

Getting started

While exploring great examples can be insightful, it’s crucial to refrain from direct replication, because those examples usually originate from well-established and large design teams, and have undergone multiple iterations. Your company’s unique circumstances, such as design maturity, business domain, and team size, may significantly differ.

For instance, in some large enterprise companies, Designers may not need to possess User Research skills as there are already dedicated professional User Experience Researchers (UXRs) within the team.

Also, navigating a sizable framework can be particularly challenging for a manager without prior experience, so my recommendation will be to start small, keep it simple, and iterate.

Planning and aligning

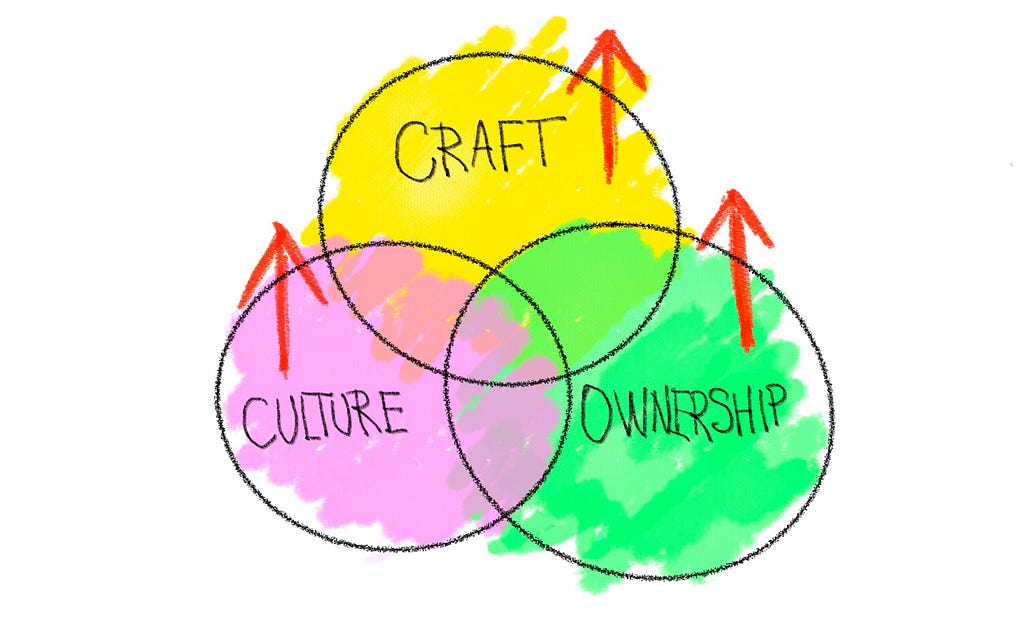

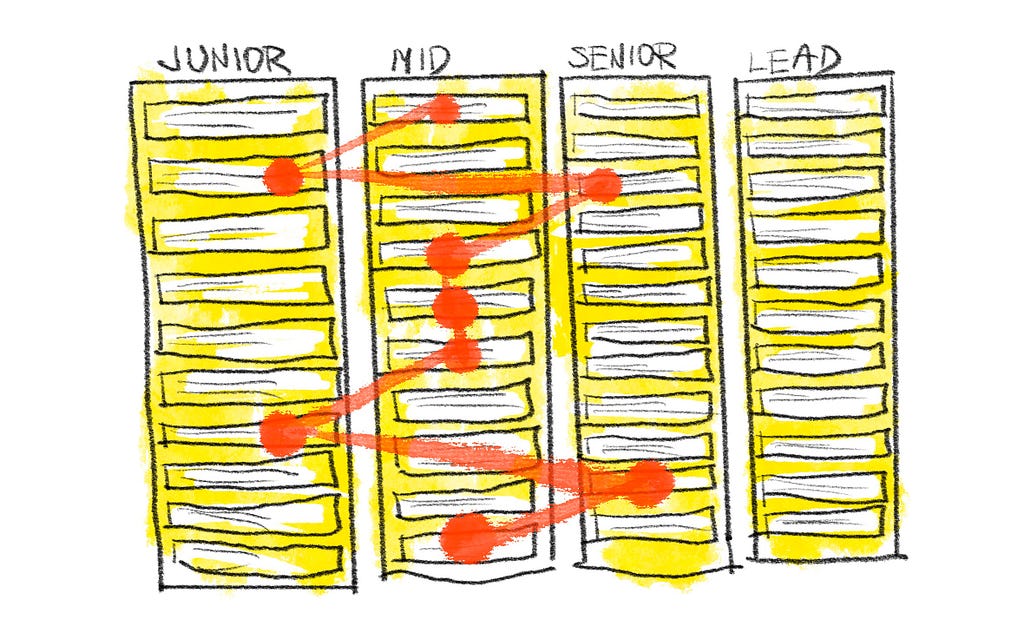

To initiate the process, consider creating a planning document where you can outline key principles for designer progression in your company. For instance, besides the Design Craft, you can also include:

- Contribution and Strategy: Evaluation of designers’ understanding of business, involvement in strategic decisions, and the significance of the domains they lead.

- Culture and Togetherness: Measuring the support and collaboration within and outside of the design team, including coaching, mentoring, and contributions to process improvements.

Align these principles with your company’s goals and culture while maintaining industry standards to ensure that seniority within your team aligns with market expectations.

Creating skills and levels

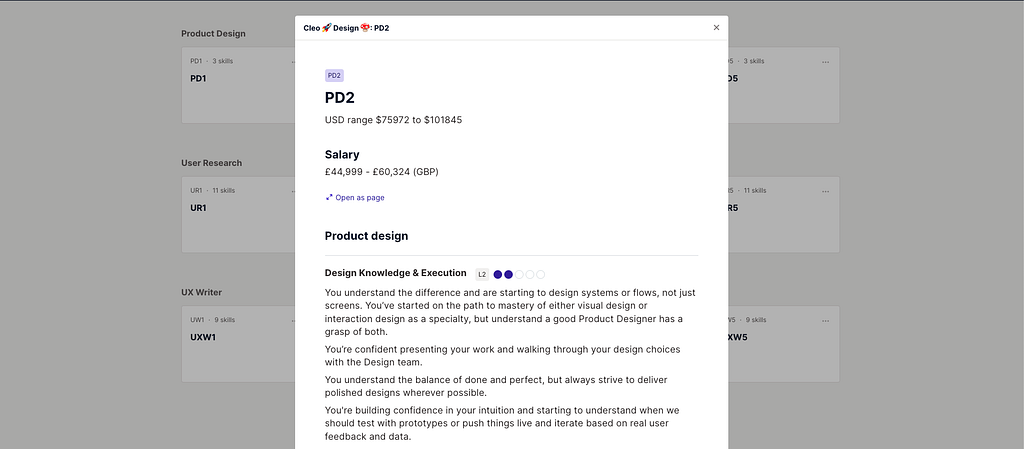

Once you’ve established and aligned the guiding principles, define specific, measurable skills to avoid ambiguity in future assessments.

It’s important to note that some skills weigh more heavily than others. For instance, some Staff Product Designers might not be the fastest prototypers but could have crucial strategic and stakeholder management skills, which are more vital for their role. Recognizing and prioritizing these skills ensures your framework accurately reflects their significance.

Also note, that some companies may hire Lead or Principal Level Designers without a clear CPF, which might lead to their undervaluation risks once your framework is ready. To ease the process, I suggest starting with Junior, Mid, and Senior levels and leaving the evaluation of higher roles for the next step.

Using the framework properly

After the framework version 1.0 is ready and approved you can use it for accessing designers’ level and crafting an individual growth plan.

Assessing designers’ levels

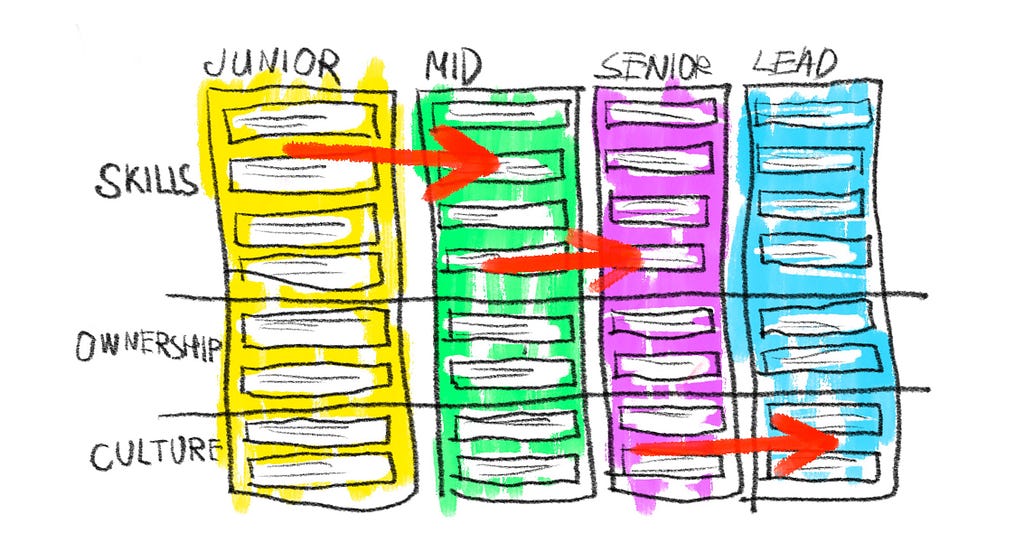

Assessment is a challenging yet crucial process. You can start with one-on-one conversations, asking designers for a self-assessment using the Framework. Let them heat-map skills with justifications, recognizing that most won’t neatly fit into one column, resulting in a zigzag pattern.

Afterward, evaluate the designers on your own or wait for colleagues’ additional input in 360 reviews. Differences in assessments may arise, prompting exploration to uncover reasons behind mismatches. Leverage your design expertise to ensure accuracy — defend designers if colleagues undervalue them, or explain adjustments if designers overvalue their skills.

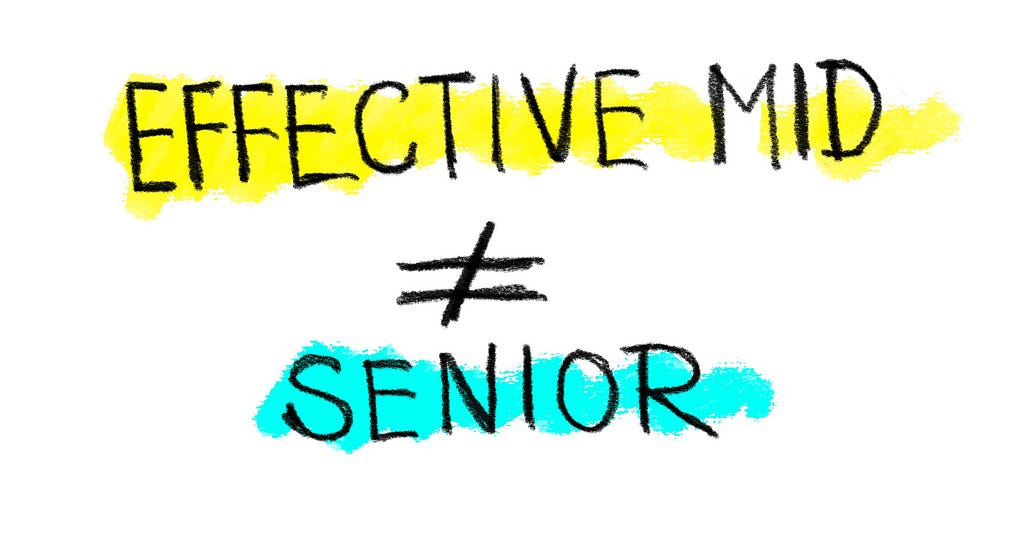

It’s crucial to emphasize once again that deciding designer levels (Mid, Senior, Lead, Principal) considers a mix of vital skills, achieved outcomes (such as meeting personal goals or Key Results), and the scale of responsibilities they can handle. For instance, someone excelling in, let’s say, user acquisition as a Senior Designer may not be ready for additional responsibilities, like managing design for both acquisition and activation. In such situations, recognizing their accomplishments through yearly bonuses or salary increases is appropriate, but postponing their promotion to Lead Product Designer until they demonstrate readiness for more extensive responsibilities is prudent.

Creating a growth plan

Once you and your designer agree on areas for improvement, you can start initiating personalized development plans.

In smaller teams, tracking progress can be done personally by you as a manager or with additional input from colleagues.

For larger teams, implementing metrics becomes valuable. For example, we can have Mid-designers who lack visual design skills, and you may spend more time guiding them (X amount more than others), so, reducing this mentoring time can become a metric to help you measure the success. Alternatively, you can also use peer reviews, where colleagues may assess the designers’ skills and set improvement goals, such as aiming to raise a visual design score from 6/10 to 8/10 after completing a relevant course within a quarter.

Avoiding mistakes

To steer clear of critical mistakes, I strongly recommend seeking mentorship. I was fortunate to receive guidance from Andrew Lobban, the VP of Product Design at Cleo (formerly Trustpilot) — a skilled design leader, an excellent mentor, and a wonderful person whom I want to acknowledge in this article for invaluable support. Acquiring mentorship can prove immensely beneficial for the smooth creation and usage of your CPF.

Additionally, consider seeking mentorship from other managers in your company who have experience in creating frameworks for their teams. Even if they aren’t specifically from a design background, their insights can provide valuable recommendations and perspectives.

Furthermore, consider utilizing a tool for creating and managing CPFs. Those tools are designed to streamline the implementation of your Career Progression Framework and enhance the overall effectiveness of your management process.

Creating and using a Career Progression Framework might seem hard and overwhelming, but trust me, it’s a big step forward in becoming a better design leader. The effort you put into it is key to your growth and success in leadership.

Thank you for reading and good luck!

Crafting a career progression framework for designers. Where to start? was originally published in UX Planet on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.