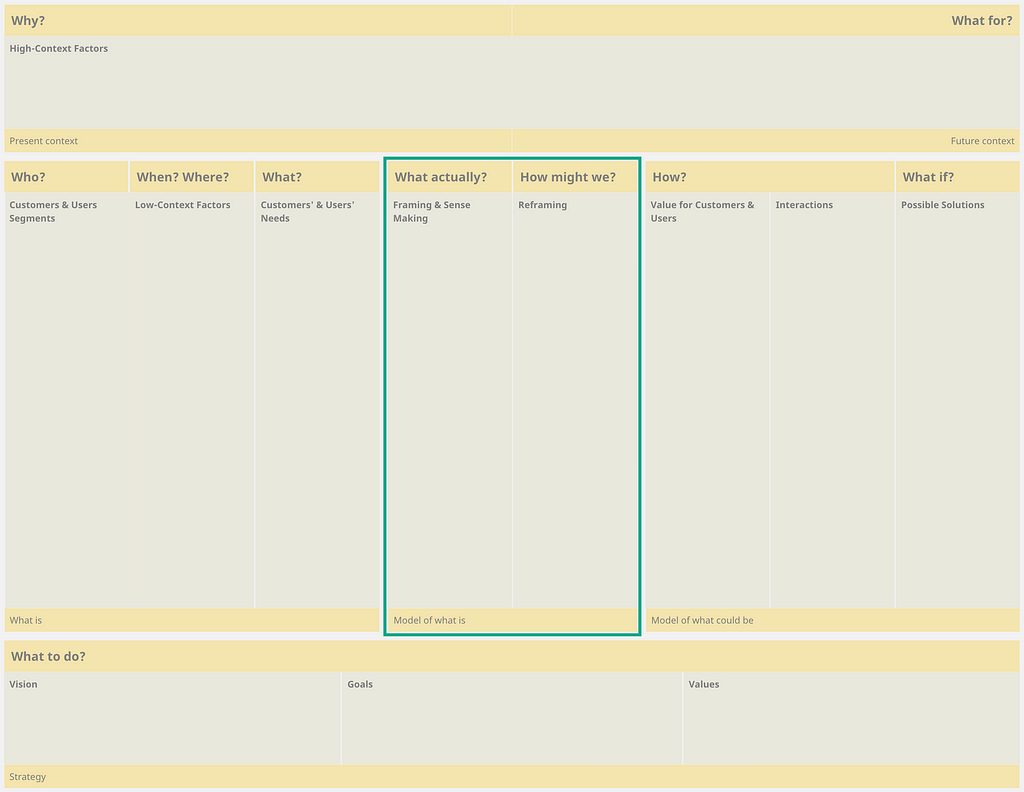

Design modeling canvas: model of what is — framing & sense making

This text describes in detail the “Model of what is” spot of the Design modeling canvas, in particular “Framing & sense making” part.

This article is a part of the series that describes the Design modeling canvas. I’ll be sharing subsequent articles in the upcoming months. Here’s the entire table of contents of the series:

- Methodological background,

- Present context & Future context,

- What is,

- Model of what is — framing and sense making,

- Model of what is — reframing,

- Model of what could be,

- Strategy.

What actually? How might we?

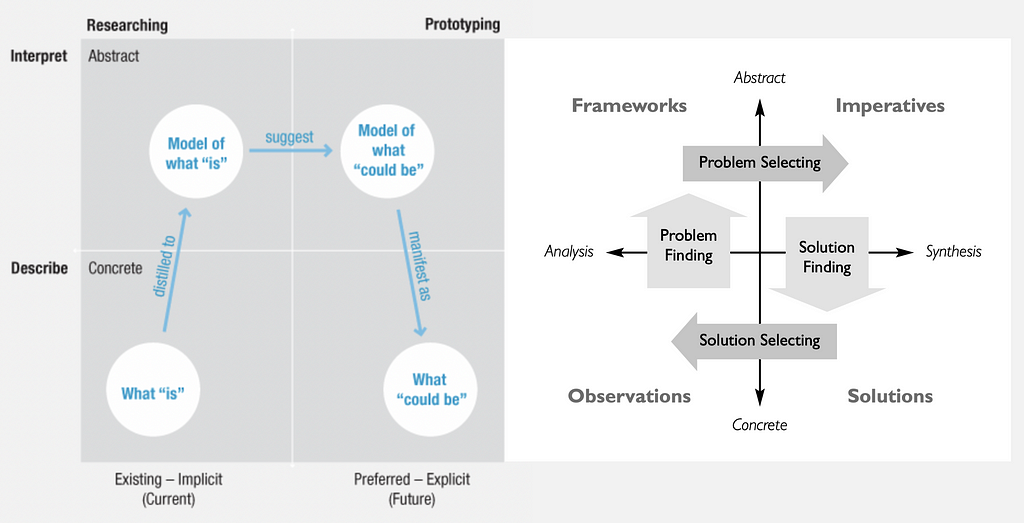

The design process moves forward from the concrete to abstract realm, from making observations to building frameworks (see below The Analysis-Synthesis Bridge Model by Dubberly, Evenson, Robinson and The Innovation as a Learning Process Beckman, Barry). While What is (or Problem finding) step of the process was meant to describe the present situation, Model of what is (or Problem selecting) is aimed at describing and interpreting (or making sense of) the present situation. Although framing and reframing activities are often prone to be performed implicitly (in one’s head) or even skipped, they deserve being externalized and elaborated in a separate spot of the canvas.

Instead of jumping straight into the Model of what could be (or Solution finding) step, it’s important to proceed with interpreting (or making sense of) research data, “organizing complexity or finding clarity in chaos” (Kolko). The purpose of this step is to come up with a model of what is, and, as a result, prepare the background for a model of what could be. “It is in the realm of abstraction — by thinking with models — that we bridge the gap between analysis and synthesis. These models are hypotheses, speculations, imagined alternatives to the concrete we started with, but they are still abstract themselves. It is easy to ‘play’ with models at this point, to test and explore” (Dubberly). Please refer to my earlier article for a bit of background around models:

Model is a result of observation, framing, and making sense of reality. Dubberly (2009) suggests that models are “ideas about the world — how it might be organized and how it might work. Models describe relationships: parts that make up wholes; structures that bind them; and how parts behave in relation to one another.” In science, models are used “to represent and increase information. The core purpose for using models is the simplification, visualization, idealization, modification, or hypothetical realization of phenomena together with the aim making the latter easier to understand.” (Hof, 2018) In other words, models are abstractions which reflect one’s understanding of the world.

As a part of the model of Innovation as a Learning Process, this step is described as follows: “Armed with the data generated from observation, the innovation process moves from the concrete to the abstract realm, attempting to make sense of the data that was collected, framing and reframing that data to extract nuggets, identify patterns, and ultimately develop a focus on what is most important to the customer or user. This step of the process requires processing a large amount of information, but at the same time being able to see what is missing for the customers and users. <…> The ultimate purpose of the framing step is to reframe, to come up with a new story to tell about how the user might solve his or her problem or to come up with a new way of seeing the problem, which in turn will allow the team to come up with new solutions.” (Beckman, Barry)

Framing & Sense Making

First, let’s define what Framing & Sense Making are.

“In design, framing can be thought of as the designer’s perspective when approaching the problem. The frame itself applies a set of exterior, subjective constraints to the design problem.” (Kolko)

“Klein, Moon, and Hoffman define sense making as ‘a motivated, continuous effort to understand connections (which can be among people, places, and events) in order to anticipate their trajectories and act effectively.’ <…> emphasis is placed on finding relationships and patterns between elements, and forcing an external view of things. (Kolko)

Framing (similar to sense making) can’t be considered as purely objective, rather, it reflects a designer’s subjective point of view which is rooted in personal assumptions and experiences. For this reason, “design is not entirely subjective, nor is it entirely objective, but it is both at different moments.” (Kolko) However, being embedded in a frame, this subjectiveness plays an important role as it allows a designer to make one’s way through complexity of a design problem towards finding a solution.

In the context of DIKW model, framing & sense making imply research data manipulation and its transformation into information and finally into knowledge about the present situation. Eventually, a designer gains understanding of the present situation. Also, a design problem can be framed at this point. However, such version of a problem statement has to be revised later during the reframing step.

Although framing & sense making are highly interrelated and can hardly be distinguished, let’s roughly split them and consider separately. As a process it looks like this:

1. Framing and making sense of the present situation:

- Transforming data into information. To start framing, a designer can “organize, manipulate, prune, and filter gathered data into a cohesive structure for information building” (Kolko). This activity allows them to set up boundaries in order to filter out what is irrelevant, forge connections between seemingly unrelated pieces of data and combine them into chunks. For this, it makes sense to be back to the Problem Finding spot of the canvas since all data have been collected over there.

- Transforming information into knowledge. Now, the focus can be moved to the Framing & Sense Making block of the canvas. Here, gained information should be interpreted or transformed into knowledge about the present situation. It is here where models emerge. “Models begin with things or events that we observe. We want to describe or explain what we see. Pieces fit together; patterns emerge; we posit causes and effects. Under this frame, evidence leads to models.” (Dubberly)

2. Framing a design problem. Findings from framing activities can now be summarized concisely in a design problem statement. “With a clearly defined problem that’s rooted in a user’s purpose, it’s easier to see what barriers are in the way of reaching that end goal.” (DeVos) Design problem statement brings focus for further design work while filtering out irrelevant and misleading ideas and fostering those that can meet the need.

Now let’s take a closer look into methods which a designer may want to use during framing & sense making.

Transforming data into information

Framing activity begins with research data manipulation and organization in order to transform it into information. “Data usually implies numbers, it simply represents discrete units of content, without context and with no organizational mechanism. <…> Information is the organization of data in ways that illustrate meaning.” (Kolko) Method that might be helpful for this sake is affinity diagramming.

Transforming information into knowledge

To continue in the direction of making sense of the present situation, gained information should be transformed into knowledge. “Knowledge results from the combination of elements of information to arrive at a principle, a theory, or a story.” (Kolko) So, the next step is to consolidate all the ingredients — Why? Who? When? Where? What? — into a comprehensive structure. Concept map or story (for instance, in the form of journey map) might be the tools of use. An essential thing about these methods is that they name entities (represented as nouns) and reveal relationships (represented as verbs) between them.

Making sense of the present situation allows a designer to produce insights. “A design insight can be thought of as the additive of problem-specific observation (‘I saw this’) and personal and professional experience (‘I know this’). This grounds an insight in both the subjective and general knowledge of the specific practitioner and in the objective data of the design problem itself. <…> An insight might manifest itself in the form of a new, subjective design constraint that you add to the problem, or it might come as an underlying philosophy and approach (a set of guiding pillars or themes that guide the creative efforts).” (Kolko) Being a “result of apprehending the inner nature of things” (Merriam-Webster Dictionary), insight is like a background element which glues pieces together in a coherent story.

I associate insight with the handful of following questions:

- What low-context factors are really essential and why?

- What attributes of customers & users are really essential and why?

- What do these people really need?

- Why is this really relevant for them in a particular context?

- How are observable things really connected with people’s beliefs and motivations?

- How are observable things really connected with high-context factors?

During framing & sense making, a designer attempts to interpret or explain the present situation, in other words, to create a new knowledge about it. What allows for creation of new knowledge is abductive reasoning which is at the heart of design synthesis. “Abduction can be thought of as the argument to the best explanation. It is the hypothesis that makes the most sense given observed phenomenon or data and based on prior experience. Abduction is a logical way of considering inference or ‘best guess’ leaps.” (Kolko) Considering the above said, making a model of what is can’t be thought of as a purely analytical activity, rather, it’s a combination of analysis and synthesis.

Framing a design problem

Finally, findings from the framing activities can be summarized in the form of so called design problem statement. To cover all the aspects of the present situation, I suggest to extend the “traditional” problem statement:

[A user] needs [need] in order to accomplish [goal].

For me it’s important to see more details for context information as well as include insights. As a template it can look like this:

When [context, When? Where?] our [user, Who?] needs a way to [need as a verb, What?] so they can [goal, What?]. It’s important because [Why?].

Design problem statement is a scoping tool that brings focus on the essential research results and guides further design work. It becomes a reference to examine the relevance of ideas and measure success of solutions that are to be proposed later. Although being based on the thorough analysis of the present situation, design problem statement can be seen from other angles, revised, and understood differently. These activities will take place on the reframing step of the process.

Thanks for reading! I’ll be sharing subsequent articles of the series in the upcoming months and would appreciate any feedback, comments, and critique.

Feel free to reach out via LinkedIn.

Design modeling canvas: model of what is — framing & sense making was originally published in UX Planet on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.