Copying success stories won’t make you successful.

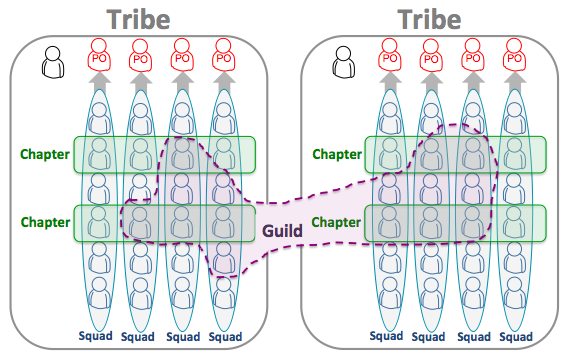

Remember the buzz around Spotify’s organizational model? Squads, tribes, chapters, and guilds. It sounded like the perfect blueprint for agile success.

The model promised autonomous teams (squads) working within larger units (tribes), connected by shared expertise (chapters) and common interests (guilds). It was a fresh take on scaling agile practices, and many companies were eager to adopt it.

We tried implementing it, but quickly realized it was too much structure for a team of 20. Just having good communication and cross-functional squads was enough. Adding more structure ended up creating redundant rituals and unproductive meetings.

We weren’t alone. ING adopted the model only to discover that layering Spotify’s model onto an existing hierarchy didn’t make teams more autonomous, it just added confusion.

Even Spotify has since moved away from the model. They acknowledged it was more of an aspirational snapshot than a scalable framework.

Why smart teams copy dumb ideas

Blindly copying practices from tech giants can do more harm than good. What works for a company like Spotify, with its unique culture and scale, might not work for you. It’s essential to critically assess whether these models fit our specific context before adopting them.

Still, we keep falling for it. Google uses OKRs, so we think we need OKRs without fully understanding what they’re about. Netflix preaches radical candor, so we start handing out unfiltered “feedback” and end up hurting everyone’s feelings. Apple does… whatever Apple does — and we try to reverse-engineer the magic.

When we hit a wall (missed deadlines, user churn, team friction) our first instinct is to look up, not around. “Let’s just do what the big guys do.”

The logic is seductive: if it worked for them, it’ll work for us. But you’re not Google. You don’t have their money, their brand, their scale, or their infinite runway for mistakes. More importantly, you don’t have their problems. They’re playing a different game. Different rules, different stakes, different board.

If you really want to learn something useful, stop listening to the winners. Talk to the ones who didn’t make it.

What the losers can teach you

You’ve heard of Airbnb and Dropbox, two of Y Combinator’s biggest success stories. But not the 95% of YC startups that quietly shut down. You’ve seen the TED Talks. But not the burnout, not the pivots, not the pitch decks that never got a second meeting.

This is survivorship bias. We spotlight the winners and forget the rest. Every unicorn buries a graveyard of startups that did everything “right” and still died. Around 90% of startups fail. Less than 1% become unicorns. But those are the ones we hear about. The shiny outliers that made it through.

Most startups follow the playbook. They raise money, build fast, talk to users, iterate. They do everything they’re supposed to do. And still, most don’t make it. Not because they were lazy, but because the odds are brutal and the variables uncontrollable.

We love the winners because they’re visible. But visibility isn’t insight. And success doesn’t prove a system works. It proves something worked once, under a very specific set of conditions.

The truth is, you can learn more from a founder who just shut down their company than from a unicorn CEO giving a keynote. The failure stories are raw. Messy. Honest. They don’t try to impress you. They just tell you what broke.

It’s not that success stories are useless. They’re just incomplete. The winners show you what’s possible. The losers show you what’s likely. And often, that’s more useful.

Success doesn’t come with a template

If a founder did X and made a billion dollars, we assume X is genius. If enough of them did X, we call it a best practice. But that’s not logic. That’s astrology with better marketing.

Just because successful companies do something doesn’t mean it made them successful. It might’ve helped. Or it might’ve been noise. Correlation isn’t causation. It’s a clue, nothing more.

Success in tech is messy. Context-dependent. Often driven by timing, taste, and luck. For every Stripe, there are hundreds of talented teams who built great products and quietly disappeared.

I’ve learned more from failed founders than from TED Talks. Not because failure is noble, but because it’s honest. It doesn’t try to sell you anything. It just tells you what broke. That’s where the real insight lives.

Don’t worship outliers. Think from first principles. Instead of asking, “What would Google do?”, ask, “What do we need, right here, with what we have?”

Use tech giant practices as data points, not gospel. Treat them like prototypes: test, discard, adapt.

You don’t need to be the next Amazon, Netflix or Airbnb. You need to be the first you. And please, stop trying to be Steve Jobs.

Stop trying to be Steve Jobs and start learning from the losers was originally published in UX Planet on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.