Beyond digital product design — how lone design generalists can un-hire themselves into more inspiring roles

The curse of knowing how to draw

Since the earliest years of my design career, when I was volunteering in organising conferences or youth activities, I was always “asked” to take care of all visual tasks — like draw a flyer or create a website. The reason was simple: creating visuals was the only easily understandable skill I had that no one else knew how to do, and it was acknowledged. While at first it was a good chance to practice, eventually this typecasting became frustrating, as it blocked me from taking on more strategic or managerial roles.

The same applies to product organisations — since creating visuals is the only clearly visible skill that no one else knows how to do, product designers are often pushed or expected to focus solely on that. Meanwhile, others take on responsibilities like defining processes, leading projects, and setting goals.

While it is great to know how to draw, it is also a terribly short career ladder for design generalists.

So is there a way out?

White hat designers

In Part 1 of this story, we explored how a lone in-house design generalist can free up time and resources by offloading routine UI maintenance tasks to web engineers. With the growing standardization of UI through reusable components and patterns, there’s little reason for generalists to be doing this work. The results may be slightly less consistent, but that’s a trade-off better addressed by hiring specialists in design systems.

So, what can a newly liberated product design generalist do with all that reclaimed time?

I could write one more story about stepping beyond product design into roles like product management, service design (or CX), or even bigger leaps into academia, research, design for government, or, who knows, politics. (If there is one field that could benefit from human-centred, as well as educated professionals, it’s that one — think of it as applying dark patterns for the public good, like white-hat designers for democracy.) But much of that has already been written elsewhere (though perhaps less about designers in politics). I’ll share links at the end.

This story, however, focuses more on how to transition on a personal level. Being a designer isn’t just a job — it’s a mindset. Moving into more business-oriented roles may require you to shift your perspective away from a user-first — or reconcile conflicting approaches. Leaving the familiar, borderless world of international tech for more local, public-sector environments — where you might be seen as an outsider — can be daunting.

So what should you look out for in that transition?

No one to talk design with

Not having like-minded people around you is one of the main downsides of being a lone design generalist — and it’s right there in the name. During hiring, the role might have been pitched as the first of many design positions to come, but that “many” may never materialize.

At first, being the only designer can even feel liberating. You define your own work process, usability patterns, and design components. You avoid long internal design discussions that often delay handoffs and frustrate other stakeholders. Finally, you get to apply all your previously gathered knowledge and experience at once, with no limitations.

But over time, especially in engineering-heavy organizations, you start to miss the designer’s mindset: the creative workshops where ideas bounce freely, the casual but inspiring community meetups, the abstract discussions, and the shared references to the broader artistic and cultural world.

If I ever take another job as a designer,

it will be in an organization where other product or service designers are already part of the team.

Otherwise, where else am I supposed to discuss everything I learned at university?

On a serious note, having other like-minded designers around can make a big difference. It allows you to share the burden of routine work (especially if engineers aren’t stepping in), while also combining your efforts and knowledge to help shift the design focus from UI execution toward customer experience and more strategic roles.

Industry to talk about

While lone refers to whether you have a team around you, generalist speaks to your career direction. As a designer, you can either specialize in a specific area, like design systems or UX research, gradually growing in seniority and eventually becoming a valued expert or consultant.

Or, you can focus on the role of design within the organization, step by step expanding its influence. Starting with product design within engineering teams, then driving the organization toward a more design-centric mindset, like expanding design into customer experience and innovation, or improving internal work processes and culture. This path defines the design generalist — someone whose career can eventually grow into strategic and managerial roles.

To follow this path, a designer needs more than strong design skills. They must also be able to contribute meaningfully to broader conversations across the organization — about the product, the service, and the industry at large.

That’s why it becomes crucial to develop real expertise in the industry your company operates in.

The best and most sustainable way to do that?

Be genuinely curious fascinated by the industry itself.

So choose wisely.

If you see your career as a design generalist, then for the long game, it’s just as important to choose the right industry as it is to choose the right company. Pick one you’re passionate about. The one you’d still want to grow in even if, one day, you drop the “designer” from your job title.

Core role to talk about

Within every organization, there are core roles and supportive roles. As a lone design generalist, you ideally want to be in a core role. Unfortunately, due to the nature of design tasks, especially in-house B2B design, it’s often viewed as a supportive function rather than core.

For example, in cybersecurity, being a cybersec engineer or researcher is a core role with better long-term career prospects, while a UI designer’s job is typically a supportive role that mostly focuses on maintaining the app’s UI. In contrast, at a large design agency, a product designer can have career-defining opportunities, whereas the cybersec IT specialist is mainly responsible for keeping the infrastructure secure and has limited potential for career growth.

Since this discussion focuses on in-house B2B designers, design agencies are outside the scope.

So, how does a core design role look in a B2B organization?

A good question. My guess is that a core design role is closely linked to industry expertise. If you, as a designer, combine strong design strategy skills with deep knowledge of the industry — enough to impact business goals beyond traditional product design — your role can evolve into a core one. That’s why working in an industry you’re passionate about is crucial for moving from a supportive to a core position.

There are also examples of temporary core roles. For instance, if a company is undergoing a major rebranding, the brand design lead may temporarily become a core role, which can help with career growth. New product launches can offer similar opportunities to product designers, including generalists. However, as the word temporary suggests, these boosts are often short-lived. If other aspects aren’t aligned, you may find yourself stuck again in the long term.

There are also ways to create momentum within a supportive role — like establishing and then managing a design system. However, much like temporary core roles, this path has its limits unless you choose to shift from a generalist position to a specialist one and build your career within the design systems domain.

It depends–no, it doesn’t

Keep “it depends”(1) for your internal dialogue. Externally, a lone product designer needs to state their opinion decisively — “this is how it should be.” That’s the kind of language the rest of the organisation understands best (unless, of course, you’re lucky enough to be surrounded by enlightened colleagues from stage 4 of the social tribe model)(2).

To become decisive, the product designer should do their homework, especially for enterprise and technology heavy products. No one wants to look like a blowhard.

Moreover, lone design generalists are often guests at the engineers’ and managers’ party, who converse in their own language, and designers are required to adapt to it.

Thus choose your battles carefully, the ones you are more confident with your knowledge, and try to minimise the indecisiveness in the ways you communicate, hence…

No more “maybe”

The time we never get

Back to a drawing metaphor. Once my schoolmates learned that I was good at drawing, they started asking me to sketch all sorts of things — portraits, anime characters, horses (for some reason, horses were a common request in the late ’90s — maybe because there was no Google to just look them up). Unless you happened to specialise in anime, caricatures, or animal illustration, after a few minutes I’d usually end up with something only slightly better than what my unartistic friends could produce — and sometimes even worse than that one anime-obsessed classmate with a notebook full of doodles. I often felt like a bit of a fraud.

While back in art school, I had a bunch of well-executed, realistic drawings — far beyond what any of my classmates could pull off, no matter how much time they spent.

The difference was time.

As an art student, you’re not a master of one style, but you’re trained in many, along with the theory behind them. To produce something great, you simply need time to apply that breadth of knowledge.

The same goes for being a generalist in product design. Sure, you’re expected to deliver a better UI than an engineer, or suggest a more sustainable UX solution than a manager — but only if you have the time to focus and go deep.

In reality, though, most work happens through last-minute requests and rushed decisions. And under those conditions, the results often aren’t much better than what the engineers or managers might have done themselves.

For a generalist — whether an art student or a product designer — the quality of your work might not stand out much in the short term. But given enough time, it improves exponentially.

The chicken or the egg

I’ve recently stumbled upon an article in the Service Design journal Touchpoint by Samin Razagh, where she pointed out the key difference in methodology and processes, despite a shared goal, between product managers and in-house service designers (which might apply even more to product designers). Designers typically follow the “double diamond” model, which from a product manager’s perspective can seem slow and non-iterative, as it takes time before reaching the development phase. Meanwhile, product managers prefer Lean and MVP thinking, which focuses on building a minimal version, releasing it, and iterating based on feedback. (3)

Both approaches are valid and have their pros and cons. The challenge for a designer lies in the tension this creates: internally — should I adopt ‘MVP thinking’ myself? — and externally — if not, how do I collaborate with product managers and engineers, especially when they’re in the vast majority?

While I agree that iterating based on real-life user feedback makes a lot of sense — and there’s little value in delaying releases — what often happens is what Russell L. Ackoff (4) described as

“Continuous improvement is the longest distance between where the organisation is and where it wants to be.”

That is, MVPs tend to be refined only incrementally by addressing smaller, more tangible user pain points, while the fundamental issues behind them often remain unchallenged due to time and resources they require. The latter would fall within the designer’s approach.

In B2B, especially, if customers keep buying and users adapt their behavior, these deeper problems might not even be seen as problems at all. This explains why, when following the product manager’s approach, a lone design generalist might start to feel their work adds little value — much like I once felt like a hack for not being able to sketch a realistic horse in five minutes, despite knowing I had well-crafted drawings back in art school that simply took more time.

First step into beyond

What may seem like a dilemma — ‘MVP thinking’ versus the ‘double diamond’ (for simplicity’s sake) — can actually be an opportunity for a lone design generalist to take a first step beyond traditional digital product design.

The key is to combine the best of both worlds.

The first step is usually the hardest, but also the most important. Regardless of whether you aim to move into product management, service design, or something entirely different, for a lone design generalist whose time and energy are largely consumed by routine UI maintenance, the key first move is to step into a more strategic role within the organisation.

Into product management

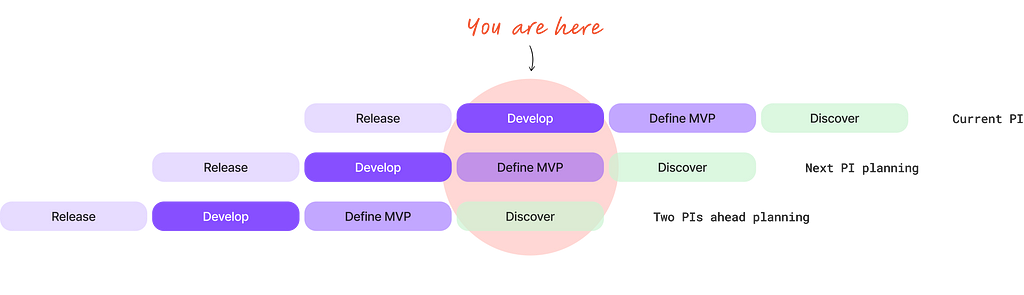

Once UI maintenance tasks are delegated to engineers (or to UI designers, if the organisation eventually hires them), the next step is to increase your strategic impact. This means stepping into the product management space while leveraging your strengths in design thinking — so instead of competing for a seat at the table, you bring unique value to it.

You can enrich the “MVP thinking” approach by implementing the “discover” and “define” phases of the double diamond ahead of time. This helps you make a stronger case for including strategic UX initiatives in the roadmap and better articulate the fundamental challenges that need solving, rather than just reacting to immediate issues.

One way to do this is by creating what I call a cascade model: take a local R&D process — which typically includes preparation, a sprint, and a follow-up — and layer it across multiple timeframes. This lets you not only see what needs to happen now from a UI design perspective, but also identify what you should focus on as a product manager, and anticipate what you’ll need to prepare for in the next strategic iteration. In essence, you’re always operating one sprint ahead.

Into customer experience

Another — or parallel — approach (since all roles we’re discussing are cross-functional hence overlapping) is to enrich customer interviews by facilitating more in-depth conversations about their experiences. This could involve showing prototypes, using brainstorming techniques, and structuring questions around different stages of the customer journey and service blueprints.

You can also take the lead in organising and facilitating workshops with internal stakeholders — whether it’s to define proto-personas or align on a product vision. Or dive into data analytics (bless ChatGPT for helping with PostgreSQL queries) to combine quantitative insights with qualitative research, laying the foundation for a more systematic user and customer research practice.

And let’s not forget — we’re talking about lone design generalists here. There are no existing CX or service design teams to transition into. But even if there were, would you genuinely want to take on a specialist role?

Whether it’s product management or customer experience, neither is a final destination here. They’re simply steps on the path to beyond: liberating your designer’s mindset from the increasingly narrow confines of tech and B2B product organisations.

Forward and beyond

If you still feel the pull to move forward and beyond roles in product organizations — into areas where you can apply your strategic design thinking to broader challenges like policymaking, executive leadership, or tackling complex societal “wicked problems” with systemic design — then my only advice is: go for it.

Some days it may feel unrealistic or unbearably slow, but good things take time. As I recently heard in an Instagram Reels voiceover:

“The long path is a shortcut, because shortcuts never lead you anywhere.”

From personal experience, there were multiple times I felt stuck or frustrated and wanted to leave my company. But I’m glad I didn’t. Staying gave me the chance to fully complete and close out that particular chapter — whether it was advocating for and adopting a design system or unifying a product portfolio.

One habit that always helps when I feel stuck: I take an online course that aligns with where I see my future heading. Completing it helps me break out of the rut, regain focus, and recharge my motivation.

And finally — please share your journey with the rest of us, aspiring lone design generalists.

What others write about it

As promised earlier, here are some stories that take a deeper dive into the transition from product design to roles like product management, academia, and other alternative career paths. They also explore the evolving role of generalists. (Apologies in advance to the authors if my brief summaries interpret their stories differently than intended — I hope I’ve captured the essence accurately.)

- Gihyuk Jeong writes about his experience pivoting his career from product design to a PhD.

- Carla M Valdes shares her observations on how the UX director role is being absorbed by product managers.

- Jorge Valencia argues that with the advent of AI, generalists are becoming more valuable than specialists.

- Meanwhile, in his LinkedIn post, Rajeev Subramanian suggests that generalist UX roles are shrinking, while offering an alternative perspective on future career paths in UX.

- Melody Koh 🤔 reflects on the current state of the tech industry and questions whether it’s time to move on.

Related stories

References

(1) NNGroup (2022), “It Depends (UX Slogan #14)” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=spR2bLNsBzE

(2) David Logan (2009), “Tribal Leadership”, TEDxTalk https://www.ted.com/talks/david_logan_tribal_leadership

(3) Samin Razagh (2025), “Service Design and Product Management in Growing Companies”, Touchpoint 16–1, pp. 22–27

(4) Russell L. Ackoff (2010), “Systems Thinking for Curious Managers”, Triarchy Press

Why we never hired a designer. Part 2 was originally published in UX Planet on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.